Why Are Some Countries Rich and Others Poor?

Indonesia. An archipelago of some 280 million souls — half of which are under the age of 30. The median age of its citizens also happens to be 30 (an industrialist’s dream). The country literally stands on top of gold mines, with vast reserves of fossil fuels, nickel, bauxite and gold. Despite such favorable cards on hand, however, the country boasts an underwhelming GDP per capita of just under USD5,000/year (116th globally).

Right across the pond is Singapore. A meek island home to a mere 6 million (fewer than Indonesia’s capital city) with no natural resources to speak of. Yet it sits on the top 10 list of the wealthiest nations on earth with a six-figure GDP per capita of about USD100,000/year.

What, then, explains such colossal delta between the two nations?

It can’t be population; mere manpower alone does not make a country rich. China and India are still envious of US prosperity despite having three times its manpower. It also can’t be natural resources — Indonesia (as well as the whole continent of Africa) should be drowning in dollars if that were the case. It also can’t be geographical location; Indonesia and Singapore are next door neighbors, and Indonesia’s other next door neighbor Malaysia is more than twice as rich in terms of GDP per capita.

So, what is it then?

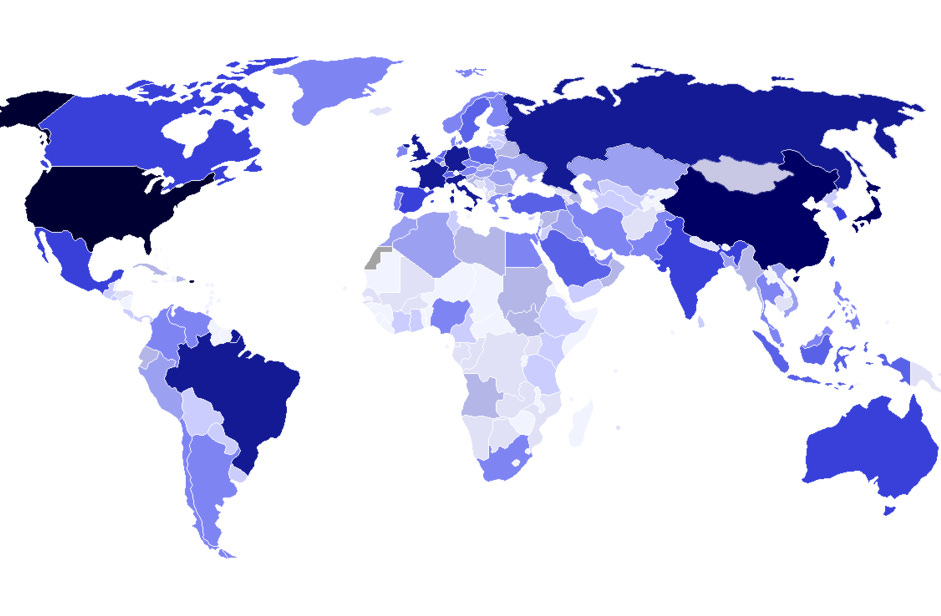

Providing a definitive answer to why some nations become prosperous — and why others do not — is the reason why Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson was awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.

Their answer to this question touches on the teachings of Scottish economist Adam Smith, in his seminal book The Wealth of Nations. The reason why some nations become prosperous, and others do not, boils down to the degree to which the country fosters the voluntary exchange of goods and services and the institutions that facilitate all such exchanges.

An economy is nothing more than a collection of human beings trading materials and services in exchange for other materials and services. Adam Smith’s contribution was in advocating the idea that the individual’s self-interest (not the government’s) is the most powerful engine of all trading activities. If the individual is left alone to his own devices, and is allowed to act fully out of his own self-interest, then he will trade in such a manner that benefits both him and the society at large, for it is in the act of benefiting others that he will benefit himself.

But a collection of individuals trading out of their own self-interest is not enough to explain why Singapore is so much richer than Indonesia. If free trade is all that it takes, then why doesn’t every Indonesian citizen simply dig out every gram of nickel and bauxite they can find and trade them with every buyer available?

For efficient trading to occur on a large scale, there must be institutions who ensure that all trading activities are done in a fair manner, a manner that provides equal opportunities for everyone involved. Fair laws and regulations must be established, schools must be built to educate all participators in the economy, and systems must be in place to enforce the spirit of fair play. This is where the 2024 Nobel Prize winners take the intellectual baton from Adam Smith.

Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson introduces us to the idea of inclusive and extractive institutions. Inclusive institutions (as the name implies) are ones that include the citizens in fostering trade activity. They encourage investment and entrepreneurship, because they allow for every participant to get their fair share of rewards commensurate with the work and risks taken. They also prevent monopolization behaviors by the elites that stifle competition and innovation.

When a nation’s institutions protect the property rights of all its citizens, punishes those who steal, educate their citizens equitably, and fairly enforces contracts; they are inclusive, and thus incentivizes and supports trading activity. When institutions are controlled by the elite few, allows for loopholes for the elite, and stifles participation and competition from others, they are extractive.

The Nobel laureates cite examples of the previously colonialized nations in Africa. Some of the poorest nations on earth today — Burkina Faso, Niger, Guinea — were once colonized by France, one of the superpowers of the West.

But the colonization was extractive in nature. ‘Property rights’ and economic participation were reserved for the elites. Enforcement of contracts were non-existent, to say the least. Educational institutions served the objectives of the colonizers and were not democratized to local citizens. The extractive nature of these institutions left countries who were blessed with ample natural resources with nothing more than rampant poverty and obsolete infrastructure today.

This is different than what occurred when the Europeans colonized North America during the 15th and 16th century. In that instance, the institutions that were established were inclusive. The Europeans created and enforced laws that protected everyone’s rights, established educational institutions that supported learning for all, and encouraged economic participation from the masses. These inclusive institutions laid the foundations for prosperity in today’s North America.

But the most glaring example of the contrast between inclusive and exclusive institutions can be seen in today’s Korean Peninsula. The two nations of North and South Korea — identical in culture, geographical location, and natural resources — split paths some 80 years ago when the Soviets took control of the North and the Americans took control of the South. The inclusive institutional culture of the United States cultivated the technological and industrial competency enjoyed by South Korea today (not to mention the exquisite freedom of expression, as seen in their booming music industry). Needless to say, the extractive institutions present in North Korea today have not birthed any slick smart phones or baby-faced boybands as of yet.

The power inclusive institutions have in generating wealth is difficult to underestimate. We have seen how the strong establishment of inclusive intuitions can transform a miniscule island in Southeast Asia into the world’s most synergetic trading hub connecting the East and the West.

The country of Singapore (as well as South Korea, Switzerland, and Hong Kong) has shown that in the presence of robust inclusive institutions; gold, bauxite, nickel or coal is no longer necessary for wealth creation. Wealth does not need to be extracted from the ground. It can also be extracted from trust — trust that is only possible in the presence of inclusive institutions.

Reducing the level of human suffering on the planet — especially unnecessary suffering — seems to be the most worthwhile endeavor any of us can take part in. And one of the ways to alleviate such suffering is to ensure a humane standard of living for every citizen in every nation. Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson have provided a blueprint for equitably building wealth in nations. Whether the leaders of poor nations will implement these important academic insights in their respective countries is, unfortunately, a question better suited for psychologists.