After graduating university with my finance and accounting degree in 2015, I worked in the treasury department at a small bank in Indonesia.

I learned a lot from that experience,

but if I can sum up what I’ve learned in one sentence, it’s this:

It’s important to manage the level liquidity and profitability of your funds.

This lesson has stuck with me and seems to come up again and again when managing my own personal funds. Liquidity and profitability are quite mutually exclusive. You cannot maximize one without minimizing the other. This balancing act is a continuous decision-making process that all of us make whilst managing our personal funds, whether we realize it or not.

Here’s my rough definition of liquidity and profitability.

Liquidity: How efficiently you can convert your assets into cash, with cash being the most liquid type of asset, by definition.

Profitability: How much your funds is returning more funds / how profitable your funds are.

Generally speaking, the more liquid the asset is, the less profitable it will be; and vice versa. Think of a current account in a bank (highly liquid account) and the low rates that they provide, as compared to a deposit account that provides a higher rate but requires a certain lock-in (less liquid) period. Or a corporate bond that usually provides a higher rate than a bank deposit, but takes more effort or cost in liquidating than a bank deposit. Usually (but not always), assets that are very liquid yield lower returns than assets that are less liquid.

In his book The Psychology of Money, Morgan Housel spells out the importance of staying wealthy versus getting wealthy. In order to get wealthy (be profitable), it’s crucial to take risks, there are no two ways about that. It is very difficult (if not impossible) to be profitable and create wealth without taking a higher than average level of risk. I think this part is intuitive for most people, there’s nothing surprising here.

What Morgan argues though, is that staying wealthy is often part of the equation that is underrated. Maintaining your funds (not losing them or putting them in high risk), surviving financially in the long term, and having the ability to gain access to your funds freely (being liquid) are valuable and often underrated skills to have in your life.

As human beings, we tend to overemphasize one part of the equation= growing our funds. We compare ourselves to others, we follow our greed and ego, and take risks in our investment decisions in order to be able to gain more profitability, often at the expense of our liquidity. Most of us perceive that high liquidity translates to low profitability, and technically that’s financially true.

What Morgan Housel argues however, is that high liquidity essentially buys you power, freedom and autonomy in the rare cases of an unexpected crisis. How rare are these crisis events? One could argue that the probability of these events are often underestimated, simply because it’s hard to imagine them happening… until they do.

Consider this fact: do you remember the last time you expected a family member to have an accident, and shortly they did?

Or the last time you expected a pandemic to happen, and it did?

Or expected a terrorist attack to occur in your city that shuts the city down, and it did?

Of course not… these events are by definition impossible to predict. But one thing that we know for sure is that unexpected events have occurred in the past, and they will continue to occur in the future. The best feeling in the world is to have plenty of liquid cash in hand in those moments to be able to get you through those events with the least possible amount of panic or despair.

“Planning is important, but the most important part of every plan is to plan on the plan not going according to plan”

Morgan Housel, The Psychology of Money

Publicly, Morgan has shared that 99% of his personal net worth basically consists of 3 asset classes: his house that he and his family currently lives in, cash, and investments in a global index funds (a well-diversified low-cost fund).

That’s it.

There is no second or third property that is currently being rented out.

There is no corporate or government bond.

There is no land bought in the hopes of capital appreciation in the next few decades.

There is no minority amount put aside for speculation on blue-chip stocks like Apple, Nike, Proctor & Gamble.

It’s just three assets: a house that they live in, a whole lot of cash, and whole lot of liquid low risk index funds.

In other words, he prioritizes simplicity and liquidity in his assets instead of trying to maximize profitability. Some financial advisors may squirm when looking at his portfolio allocations and see a large opportunity cost for profitability due to the high amount of what they might call ‘idle funds’ or ‘underutilized assets’, but Morgan sees it more as an insurance policy against unexpected events and buying peace of mind.

I’ve experienced a taste of this ‘unexpected event’ recently in my life. Although it wasn’t necessarily a crisis (and everyone in my family ended up perfectly okay), but it did give me a little bit of a scare in the moment.

About a year ago my parents went on holidays to Europe. It was a 14-day trip. Bear in mind that we reside in Indonesia, so Europe is a very long way away from home.

Within the first day of the trip I got a text from them informing me that there were issues with their credit card and that they needed me to send 100 million rupiah (about 7,000 USD) just in case they would need the cash in the scenario that they wouldn’t be able to sort out their credit card issue in the near future.

In terms of my total assets, I had more than enough to be able to cover that amount. However, in terms of cold hard cash, I was a bit short at that moment. At that time, I was undergoing renovations and repairs on a particular property that we were planning to rent out, and thus I needed to sell (liquidate) some of my stocks in order to be able to send those funds to my parents in Europe immediately.

Luckily, my stock portfolio was currently making money (they weren’t underwater), so I had no hard feelings liquidating them and actualizing some profits. If those stocks were underwater however, then I would be forced to take the hit and actualize some financial losses in order to be able to help out my folks who were currently having some financial trouble in another continent.

Here’s an important and nuanced point by Morgan Housel that I appreciate:

By holding on to a lot of cash, you might think that you’re losing some percentage points of potential profitability from not investing in more risky and less liquid assets (such as stocks, bonds, or gold). However, by the same token, having a lot of cash will allow you to not have to liquidate your bad investments in times of crisis.

You see, I was lucky that my stocks were up at that moment, but if my stocks were underwater, I would have wished that I had more cash on hand so that I wouldn’t not be forced to sell my stocks. That’s the whole point of having a large amount of cash, it allows you to have power and autonomy in ‘crisis’ situations whilst not having to sell the remainder of your investments that may not yet be on the green. Think of the opportunity cost of higher returns as the price that you pay for this power and autonomy in times of crisis.

So be sure to think more deeply about the power of having liquidity. Liquidity is usually an underrated power. It’s underrated because it acts like an insurance policy=

It is difficult to measure its value until something bad happens.

Since that valuable learning experience, I have increased the amount of cash as a proportion of my portfolio.

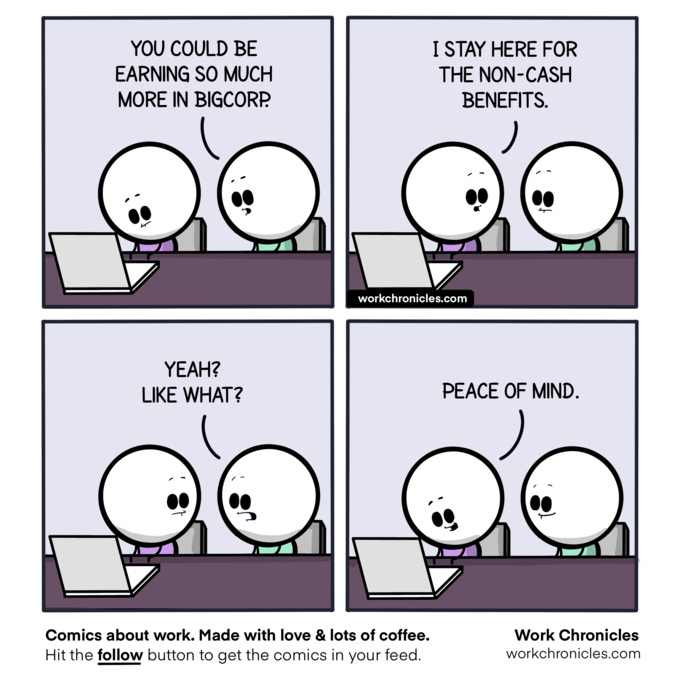

I sometimes still see them as ‘idle assets’ that are losing valuable potential of earning more returns, but intuitively I now know that I have greater power and autonomy in cases of emergency in the future.

That gives me peace of mind.