Do Presidents Control The Economy?

The surprisingly limited economic influence of the commander-in-chief

What could be a more compelling reason to vote for a presidential candidate than the promise of putting more cash into your pocket? Not much. According to Chat GPT, research suggest that voters tend to prioritize economic concerns over societal concerns in their voting choice in times of economic crisis (as one might expect). In the last US presidential election, two-thirds of voters claimed that the “economy was on the wrong track”, which may partially explain Trump’s recent definitive victory not only in the electoral college but also the majority vote. There is no surprise that when the economy is grumbling, voters grumble along with it.

What is surprising, however, is how much influence presidential candidates purport to have over the economy. Promises such as lowering income taxes and increasing tariffs (as given by Trump) or lowering prices of housing and groceries (as given by Harris) are typical. But they also grossly overexaggerate the extent of presidential decree over the issue.

The power that any sitting president has over the economy is, at best, limited. At least in the United States, checks and balances are such that no single individual in government (not even the President him/herself) can act as a singular puppet master over the economy.

It Takes a Village

There are two major levers regulators use to influence the state and trajectory of the economy: monetary policy and fiscal policy. Monetary policy involves controlling the money supply in the economy. When the growth of the general level of prices (inflation) is too high, money supply must be reduced in order to temper high prices. When inflation is too low, money supply must be increased in order to stimulate price growth.

Fiscal policy involves controlling the money collected and spent by the government. The government decides how much money they will extract from corporations and individuals (through taxes) and how much money to spend on corporations and individuals (government spendings). The commonality between these two powerful levers of the economy is that they rely very little on the decision-making powers of the President.

Monetary Policy

Not only does monetary policy rely very little on presidential decree, but monetary policy is also expected to be non-partisan. In fact, central bank independence (the degree to which the central bank is free from political influence) is seen as a crucial property of a nation’s monetary governance. The reason for this is simple: if central banks were politically motivated, then interest rates would never stop going down. Rates would continuously reduce in order to appease the pockets of voters — which is unsustainable practice for the economy as a whole.

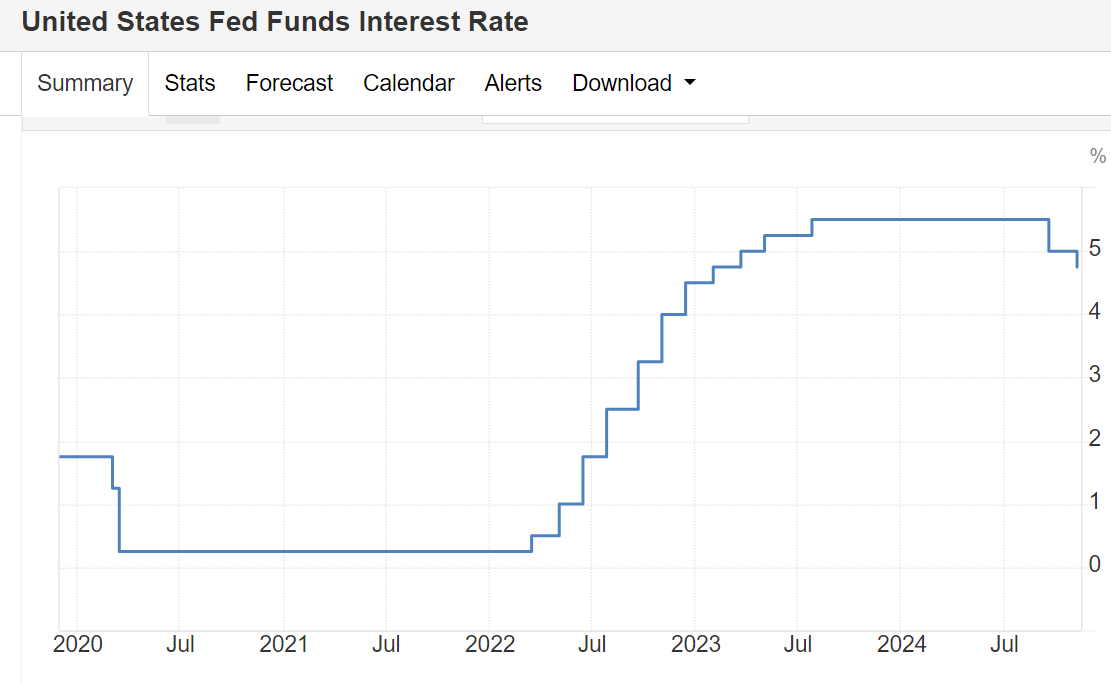

The independence of the central bank allows for rates to increase and decrease not for the appeasement of voters’ pockets (i.e. not for any political reasons), but for the health of the economy as a whole. This is precisely what occurred during early 2022 to mid 2023 when interest rates skyrocketed from virtually zero to 5.5% in the fight against rampant post-COVID inflation. Jerome Powell increasing interest rates to record-highs did nothing to support Biden’s popularity (in fact, they damaged Biden’s approval ratings), but they were necessary steps taken by the Central Bank to control inflation.

When it comes to monetary policy, the president’s influence is simply on the appointment of the chair of the Federal Reserve, and pretty much nothing else. The President cannot even fire the Fed chair (with the exception of extra-ordinary circumstances), let alone direct them on their monetary policy choices. When Trump says things like “Interest rates were much lower during my presidency!”, we should bear two things in mind. Number one: he’s right, but number two: it wasn’t because of him.

Fiscal Policy

The president has more of a role when it comes to fiscal policy, but again, his/her role is limited. The decision on how much money to raise from and how much money to spend on the private sector first lies in the collective decision of Congress. Congress consists of 535 voting members — 100 of them called the Senate and the remaining 435 called the House of Representatives. For a tax/spending bill to be passed through Congress, it must be voted on by both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Only then does it come to the president’s table for approval.

If the president refuses to approve the bill, then it becomes a back-and-forth exercise of amending and negotiating between the president and Congress. Some bills receive easy bipartisan support from Congress and get approved very quickly by the president (such as the COVID-19 relief bills that were passed within a few weeks). Some bills create more friction, not only between the president and Congress, but also within the members of Congress itself. According to Chat GPT, bills that eventually become law are usually passed within a few months to a year. But an overwhelming majority of bills (90%) are lost in the political ether, never to be made law due to the irreconcilable differences between all the parties involved.

One of Donald Trump’s major and most controversial promises during his latest campaign was to drastically cut both corporate and income tax while drastically increasing tariffs. This protectionist policy goes hand-in-hand with his “America First” ideology he has held since day one in the White House. Will he actually go through with this audacious promise?

Well, the Republican Party had just taken majority control of the 100 seats in the Senate, and is currently very close to winning the majority of seats in the House of Representatives. Trump’s proposed tax policies do require a lot of voting and approvals from Congress, but by the way things are unfolding for the Republican party, it seems like he will get all the legislative support he can get in his second term as president.

Though interest rate oscillations are largely outside of the president’s control, taxes and government spending are not — so long as the president garners the support of Congress. The next time Trump makes claims on US interest rates, best not to put much (if any) weight on his words. But the next time he makes claims on fiscal issues, best to take his words a little more seriously.