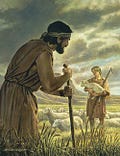

One of the most well-known allegories in the Bible is that of Cain and Abel. The story is only a few paragraphs in length, but it can offer a lifetime’s worth of pondering from its depth.

This story is powerful because it very forthrightly highlights the absolute pettiness and destructiveness of human behavior that can be born from a state of envy. It illustrates just how dark envy can push one to become.

In summary, the story goes like this:

Cain was in charge of the soil, whilst Abel the flocks.

Upon their offerings to the Lord, Cain offered fruits from his works from the soil. Abel offered portions of his first-born flock.

The Lord was favorable towards Abel’s offerings, but was not favorable towards Cain’s offerings.

Upon witnessing Cain’s distress, the Lord said:

“Why are you angry? Why is your face downcast? If you do what is right, will you not be accepted? But if you do not do what is right, sin is crouching at your door; it desires to have you, but you must rule over it.”

Despite receiving this message from the Lord, Cain attacked his brother Abel, and killed him.

We all have felt envious before, and I think we can all instinctually feel the pettiness of such a state of mind. Psychologist Paul Bloom called envy the worst of the seven deadly sins, because unlike the other six ([1] pride, [2] greed, [3] lust, [4] gluttony, [5] anger and [6] laziness), envy does not even feel good!

Think about it: pride, greed, lust, gluttony, anger, and laziness may indeed earn you a one-way ticket to eternal damnation in hell — but at the very least you can subjectively feel good along the way (yes anger can actually feel good, because it can make you feel self-justified, self-righteous).

But envy has no subjective positive value whatsoever. As Paul Bloom puts it, envy just “hurts”. Envy just leaves you with a prickling sensation of shame, frustration and/or anger towards your lack of possessions/achievements compared to the other.

And here is the most interesting nuance when it comes to envy: we are always envious of people who we can reasonably compare ourselves to.

This is the paradox of envy: we always feel ‘lesser’ to the people who are somewhat ‘at our level’. The further apart they are from our parameter of comparability, the less likely we are to develop a sense of envy towards them.

Who are you more likely to be envious of: The Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia — or your high school friend who is doing 10x better than you? The answer is (by far) your high school friend, in spite of the fact that Mohammed bin Salman is probably wealthier than the two of you combined, times a gazillion.

The people who are most envious of the super-rich are not the super-poor — but the not-as-rich. The people who are most envious of Ferrari-drivers are not bicycle riders — but Mercedes drivers

Author and philosopher Alain De Botton puts it beautifully when he said: “The reason why we’re not jealous of the Queen of England is because she’s too weird”. She is just too far removed.

Although The Queen of England, or Bill Gates, or Paul McCartney is much richer than any of us will ever be, they probably do not annoy you as much as that d*ickhead from work who always seem to get promoted instead of you.

Part of the reason that Cain was so envious of Abel was because Abel was extremely close to his parameter of comparability. I mean — Abel was his brother for God’s sake (forgive the pun).

With such close proximity and comparability, any slight schisms of outcome between the two are sure to induce a state of envy.

The unconscious logic of the envious is this: I feel that I am so similar to you — so why don’t I have what you have?

The Illusion of Comparability

Isn’t it peculiar that there is one bucket of people who we insist upon comparing ourselves to — and another bucket of people who we will never fathom comparing ourselves to?

Your siblings, your co-workers, people of similar age, your high-school friends — all fit under the category of ‘people I can compare myself to’. Yet The Prince of Saudi Arabia and the disease-ridden beggar in Bangladesh do not get a seat in this mental cathedral of yours.

I argue that these two buckets (like many things in life) are simply a figment of our imagination. It is an illusion, or at least an irrational story, to assume that ‘this group of people is comparable to me’, and ‘that group of people is not comparable to me’, and therefore, ‘It makes sense for me to be envious of one — but not the other’.

The fact of the matter is: none of us have the slightest access to anyone else’s thoughts, five senses, emotions and memories (this is not some magical philosophical one-liner, it is merely a basic dumb fact).

We do not compare ourselves to the Queen of England because she is obviously very far removed from our day-to-day experience. But to assume that you know the texture of your high-school friend’s thoughts, emotions, and five senses better than you know the Queen’s is an illusion. You can probably guess more accurately — but it is impossible for one to know exactly, because it is impossible to share one another’s consciousness.

The inner life of your high-school friend (or anyone else you are comparing yourself to) is just as a mystery to you as the inner life of the Queen of England. There are no two buckets of people (one you can compare yourself to, and one you cannot compare yourself to). There is only one bucket: People.

When you place everyone into a single bucket — a bucket labelled “unknowable mystery” — envy will naturally subdue as a consequence of the lessening of your propensity to compare.

So, what happened to Cain? Where did his state of envy lead him to?

After killing his brother Abel in a rage of envy, Cain realized the atrocity of what he had done, and surrendered himself in front of God to a life of banishment and death.

“I shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth, and anyone who meets me may kill me.” — He said.

But interestingly, the Lord put a ‘mark’ on Cain, ensuring that anyone who kills him will suffer vengeance seven times over.

You see, Cain was not even allowed to release himself from the atrocity of his bad deed through the sweet release of death. Instead, he was forced to roam around the earth and ‘live with what he had done’. To ‘live with himself’, so to speak.

What a punishment. And what a story.